Engines: A Key Enabling Technology

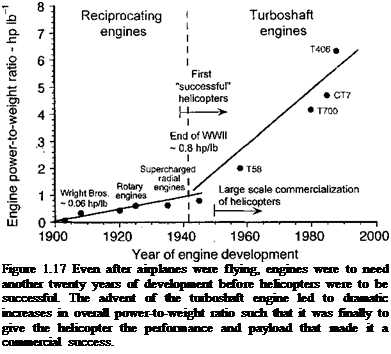

The development of the engine (powerplant) is fundamental to any form of flight. While airplanes could fly with engines of relatively lower power, the success of the helicopter had to wait until aircraft engine technology could be refined to the point that much more powerful and lightweight engines could be built. A look at the historical record

(Fig. 1.17) shows that the need for engines of sufficient power-to-weight ratio was really a key enabling technology for the success of the helicopter.

![]()

|

‘ I V fVia anfltг ІІлa і*отііі*лг1 ТґЛТ’ оПЛі »-v v ■ і ■ ■

xu tills taujf tilt/ puwvi ivvjuiitu ivi ouvwoutui quantity and an understanding of the problem proceeded mostly on a trial and error basis. The early rotor systems had extremely poor aerodynamic performance, with efficiencies (figures of merit) of no more than 50%. This is reflected in the engines used in some of the helicopter concepts designed in the early 1900s, which were significantly overpowered and very overweight. Prior to 1870, the steam engine was the only powerplant available for use in most mechanical devices. The steam engine is an external combustion engine and, relatively speaking, it is quite a primitive form of powerplant. It requires a separate boiler, combustor, recirculating pump, condenser, power producing piston and cylinder, as well as fuel and an ample supply of water. All of these components would make it very difficult to raise the power-to-weight ratio of a steam engine to a level suitable for aeronautical use. Nonetheless, until the internal combustion engine was developed, the performance of steam engines was to be steadily improved upon, being brought to a high level of practicality by the innovations of James Watt.

The state of the art of aeronautical steam engine technology in the mid-nineteenth century is reflected in the works of British engineers Stringfellow and Hensen and also the American, Charles Manly. The Hensen steam engine weighed about 16 lb (7.26 kg) and produced about 1 hp (0.746 kW), giving a power-to-weight ratio of about 0.06, which as about three times that of a traditional steam plant of the era. Fueled by methyl alcohol, this was also a more practical fuel for use in aeronautical applications. However, to save weight the engine lacked a condenser and so ran on a fixed supply of water. With a representative steam consumption of 30 lb/hp/hr (18.25 kg/kW/hr) this was too high for aircraft use. A steam engine of this type was also used by Enrico Forlanini of Italy in about 1878 for his experiments with coaxial helicopter rotor models.

In the United States, Charles Manly built a relatively sophisticated five cylinder steam engine for use on Langley’s Aerodrome. The cylinders were arranged radially around the crankcase, a form of construction that was later to become a basis for the popular air-cooled radial reciprocating internal combustion aircraft engine. Manly’s engine produced about 52 hp (36.76 kW) and weighed about 151 lb (68.5 kg), giving a power-to-weight ratio of

0. 34 hp/lb (0.56 kW/kg). The Australian, Lawrence Hargreve, worked on many different engine concepts, including those powered by steam and gasoline. Hargreve, along with the Berliners, was one of the first to devise the concept of a rotary engine, where the cylinders rotated about a fixed crankshaft, another popular design that was later to be used on many different types of aircraft, including helicopters.

The internal combustion engine came about toward the end of the nineteenth century and was a result of the scientific contributions from many individuals. Realizing the limitations of the steam engine, there was gradual accumulation of knowledge in thermodynamics, mechanics, materials, and liquid fuels science. One of the earliest studies of the thermodynamic principles was by Sadi Carnot in 1824 in his famous paper “Reflections on the Motive Power of Heat.” In 1862, Alphose Beau de Rochas published the first theory describing the four-stroke combustion cycle. In 1876, Nikolaus Otto was to use Rochas’s theory to design an engine that was to form the basis for the modem gasoline-powered reciprocating engine. The development of the internal combustion engine eliminated many parts, simplified the overall powerplant system and for the first time enabled the construction of a compact powerplant of relatively high power-to-weight ratio suitable for an aircraft.

The earliest successful gasoline-powered aircraft engines were of the air-cooled rotary type. The popular French “Gnome” and “Le Rhone” rotary engines had power-to-weight ratios of 0.35 hp/lb (0.58 kW/kg) and were probably the most advanced lightweight engines of their time.[8] This type of engine was used by many helicopter pioneers of the era, including Igor Sikorsky in his test rig of 1910. The rotary engine suffered from inherent disadvantages, but compared to other types of engines that were available at the time, they were smooth running and sufficiently lightweight to be suitable for aircraft use. One major technology to enable vertical flight, the powerplant, was now finally at hand.