RATING OF HANDLING QUALITIES

To be able to assess aircraft handling qualities one must have a measuring technique with which any given vehicle’s characteristics can be rated. In the early days of aviation, this was done by soliciting the comments of pilots after they had flown the aircraft. However, it was soon found that a communications problem existed with pilots using different adjectives to describe the same flight characteristics. These ambiguities have been alleviated considerably by the introduction of a uniform set of descriptive phrases by workers in the field. The most widely accepted set is referred to as the “Cooper-Harper Scale,’’ where a numerical rating scale is utilized in conjunction with a set of descriptive phrases. This scale is presented in Fig. 1.4. To apply this rating technique it is necessary to describe accurately the conditions under which the results were obtained. In addition it should be realized that the numerical pilot rating (1-10) is merely a shorthand notation for the descriptive phrases and as such no mathematical operations can be carried out on them in a rigorous sense. For example, a vehicle configuration rated as 6 should not be thought to be “twice as bad” as one rated at 3. The comments from evaluation pilots are extremely useful and this information will provide the detailed reasons for the choice of a rating.

Other techniques have been applied to the rating of handling qualities. For example, attempts have been made to use the overall system performance as a rating parameter. However, due to the pilot’s adaptive capability, quite often he can cause the overall system response of a bad vehicle to approach that of a good vehicle, leading to the same performance but vastly differing pilot ratings. Consequently system performance has not proved to be a good rating parameter. A more promising approach involves the measurement of the pilot’s physiological and psychological state. Such methods lead to objective assessments of how the system is influencing the human controller. The measurement of human pilot describing functions is part of this technique (Kleinman et al., 1970; McRuer and Krendel, 1973; Reid, 1969).

Research into aircraft handling qualities is aimed in part at ascertaining which vehicle parameters influence pilot acceptance. It is obvious that the number of possi-

|

ADEQUACY FOR SELECTED TASK OR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

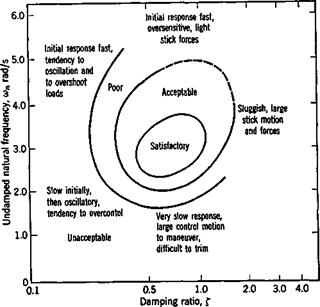

Figure 1.5 Longitudinal short-period oscillation—pilot opinion contours (O’Hara, 1967). |

ble combinations of parameters is staggering, and consequently attempts are made to study one particular aspect of the vehicle while maintaining all others in a “satisfactory” configuration. Thus the task is formulated in a fashion that is amenable to study. The risk involved in this technique is that important interaction effects can be overlooked. For example, it is found that the degree of difficulty a pilot finds in controlling an aircraft’s lateral-directional mode influences his rating of the longitudinal dynamics. Such facts must be taken into account when interpreting test results. Another possible bias exists in handling qualities results obtained in the past because most of the work has been done in conjunction with fighter aircraft. The findings from such research can often be presented as “isorating” curves such as those shown in Fig. 1.5.