WORLD WIDE WEB RESOURCES

|

|

The World Wide Web is an aviation enthusiast’s dream. It features hundreds of excellent Web pages that present credible, responsible information on every aspect of aviation. But the Internet is a freewheeling, evanescent medium that allows one person’s ideas to be placed on a level ground with everyone else’s.

That’s why, no matter what pages I find interesting, you should regard their content with prudent skepticism. The content they presented when I visited them may have changed, even disappeared.

With those cautions and caveats, which are no more than common sense to those of us who turn to the Internet for more and more of our information, here are some Web sites I found interesting, even if I didn’t buy into everything they had to say.

Aviation History

www. first-to-fly. com/

Here’s the full story of the Wright brothers’ historic first flight, told with the perspective and scholarship of the Wright Brothers Centennial Museum Online. For teachers and aviation history buffs, this is the Web’s best Wright brothers’ site.

aeroweb. brooklyn. cuny. edu/history/wright/first. html

This is the account, in Orville’s own words, of what led up to the first flight of a man-controlled, powered airplane. From the glider test flights to the inevitable mechanical failures to the final successful flight, this is the account from the man who shared a place in history as the first flyer.

aerofiles. com/chrono. html

This site’s designers say it’s still being completed, and if so, we have something special to look forward to. This is a good, though not comprehensive, chronology. It skims over the last three decades, but makes up for it with an excellent store of entertaining, informative biographies. The Aerofiles home page (aerofiles. com) is also worth visiting.

www. aviation-history. com

This site is a treasure trove for fans of real-life histories, many of which are featured under the “Airmen” link. What’s more, there are few sites anywhere else on the Web where you’ll find such excellent photos of such obscure airplanes. It’s the only site I’ve seen that includes a photo of Great Britain’s vintage Bristol Beaufighter— not that I was looking for one. Still, this site features some serious history that’s found in very few other places, on the Web or off. The sound file will drive you out of your gourd after a few “passes” of the war bird whose growling engine is part of the site’s multimedia package. Wait a few minutes and it will stop, or just click the Stop button on your browser to silence it.

www. hq. nasa. gov/ofBce/pao/History/SP-468/cover. htm

If you’re a true student of aviation history, and not just looking at the pictures, here’s a site worth your time. But bring a notebook, a No. 2 pencil, and one of those pink erasers, because this site can convince you you’re going back to school. After a few minutes, you’ll find that you’re being rewarded with some of the best analysis of how aviation has steadily evolved into a sophisticated science. By the way, this is a government site, so don’t expect any flash and glitz. It’s all business, and very sound business at that.

members. tripod. com/usfighter/

Yes, this is one of those annoying Tripod member sites that insists on forcing pop-up windows down our throats. Simply minimize, but do not close, the first one and you won’t be bothered any longer. Once past the pop-up, the site has its value. It features photos and histories of the aces of America’s air wars and the airplanes they flew. The site is professionally presented, even though it is hosted by Tripod. By the way, if you have not gotten your fill of John Gillespie Magee Jr.’s maudlin verse “High Flight,” you can read it here, along with a brief biography of the unfortunate author.

www. nationalaviation. org/inductee. html

Amateurishly constructed, this site can boast only one virtue: It features excellent biographies of some of the greatest figures in aviation. The write-ups of heroes range from aviation publishing giant Elrey Jeppesen to T. Claude Ryan, the man whose company built Charles Lindbergh’s The Spirit of St. Louis. Aviation has some of the greatest and most courageous characters to be found, and these biographical sketches succeed in bringing them alive. This is a “don’t-miss” destination for the aviation history buff.

www. thehistorynet. com/THN archives/AviationT echnology

Here’s a fair warning: Don’t visit this site unless you have hours to devote to learning the history of aviation, and more. The aviation portion is excellent in itself, but it’s part of an online history undertaking that will hold armchair historians in thrall for hours at a time. The tragic life of Ernst Udet, the World War I ace and partial inspiration for the film The Great Waldo Pepper, is one of the finest stories on the great pilot I’ve ever seen. All the content on this site is of the highest quality—a joy to visit.

www. airmailpioneers. org/

A good starting point for learning about the most daring of all pilots, I would argue—the air mail pilots who braved wicked weather, treacherous equipment, and callousness toward safety that causes modern pilots to blanche.

www. centercomp. com/dc3/

An excellent resource for information on the most important aircraft ever made. A case could be made that the almost indestructible DC-3 was the first airplane airline passenger trusted to carry them safely. Berliners, for their part, will never forget the C-47, as the military calls the DC-3, because during the long months of the Berlin Air Lift, its blunt nose and growling engines meant food, life, and survival. The site also serves as a meeting point for the community of airplane builders, pilots, and lovers of the airplane Gen. Dwight Eisenhower called one of the four most important weapons of World War II.

www. swizzle. com/panam. htm

This personal page by Rick Bollar is a good resource about all things Pan Am, from its heyday in the era of the great Clipper Ships to its darkest hours following the Lockerbie bombing and its ultimate demise in bankruptcy and disgrace. Now, the greatest name in airline history is making a comeback. If it pertains to Pan Am, you’ll find it here.

www. tighar. org/

No other group has been as dedicated—or should I say obsessed?—with the mysteries surrounding the disappearance of Amelia Earhart as TIGHAR. This Web site lets us all wallow in the murky pool, though with more scholastic research and less wackiness than others might bring to the subject.

www. thehistorynet. com/AviationHistory/articles/1997/00797 cover. htm

C. V. Glines, the excellent aviation historian, beautifully spins a concise biography of Earhart. This is all you’ll need to know to hold your own in a cocktail party debate over Earhart’s fate.

www. pig. net/~stearm an/airshow/wind. html

A delightful tidbit of barnstorming lore. Don’t miss “Lisa’s Rules for Wingwalking,” with special attention to the first and the last rules. www. deepsky. com/~mango/gustave/Pages/article8.html

Not many have the audacity to publicly confess a manic obsession with the first-flight claims of Gustave Whitehead, but the creators of this site do. Here you can find more testimony than you’d ever thought existed on claims that the Wrights were the second to fly—some of it compelling.

www. worldbook. com/fun/aviator/html/av6.htm

From the folks at World Book Multimedia Encyclopedia, this is a good reference site on the life and career of Charles Lindbergh. www. lindberghtrial. com/

More concerned with the Lindbergh kidnapping than Lucky Lindy’s life and career, this site nonetheless provides a comprehensive coverage of the greatest tragedy in the life of America’s most famous flying hero.

www. pbs. org/wgbh/amex/lindbergh/index. html

As you’d expect, PBS is behind the best Lindbergh site on the Web. It’s all here, and with authority. www. richthofen. com/rickenbacker/

Here’s the complete text of Eddie Rickenbacker’s classic memoir, Fighting the Flying Circus. Rickenbacker knew better than anyone what World War I flying was about, and he tells it in his own words.

www. cfanet. com/mlewis/

A very rich, compelling resource for World War I aviation, though hamstrung by a clunky home page. Do the work required to dig into each category, because every vein yields a golden nugget.

www. richthofen. com/

Here’s the complete text of The Red Fighter Pilot, by Manfred von Richtofen, the infamous Red Baron. Richtofen was a complex and thoughtful man who foresaw his early death and was haunted by it.

www. worldwar1.com/

This comprehensive site is a history text in itself, though more readable than most. It places the air war in its proper context in one of the deadliest conflagrations of the twentieth century.

www. mustangops. com/legends/yeager. html

Brief, photo-rich biography of Chuck Yeager, a war hero who went on to help pioneer modern aviation. www. thehistorynet. com/AviationHistory/articles/1997/01972 cover. htm

Another C. V. Glines great going inside the cockpit and bomb bay of Bockscar, the B-29 that dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

Aerobatics and Air Shows

acro. harvard. edu/IAC/acro_figures. html

Like a book that reveals the magicians’ secrets, this site unveils the secrets behind aerobatics. Aside from Neil Williams’ classic book, Aerobatics (see Appendix C, “Recommended Reading), this is probably the most clear and concise explanation of aerobatics maneuvers you’re likely to find.

www. am-tek. com/WorldFederationOfAirshowCongress/airshowact. htm

For the incurable air show junkie, here’s the lowdown on all your favorite performers. www. airshows. com/

Presents still more air show lowdown. www. blueangels. navy. mil/

This site covers the Navy’s Angel Demonstration Team in more detail than you’d ever want to know. www. nellis. af. mil/thunderbirds/default. htm

The Air Force’s Thunderbirds Demonstration Team has a Web site that’s almost as thrilling as their performances.

Ballooning and Blimps.

www. launch. net/

From the basics of ballooning theory to weather to auctions where balloonists can buy their own bags of hot air, this site is the place—an excellent resource. www. aibf. org/

The greatest balloon festival has the greatest Web site, with stunning, high-resolution photographs of previous fiestas and information about coming ones. www. lakehurst. navy. mil/web99/hindenb. html

Going up in flames is not a major concern for modern balloon and blimp pilots, but it used to be. Here’s a story of the worst aviation disaster the world had seen when it occurred in 1937. Listen to the chilling audio account if your nerves can stand it.

www. goodyear. com/us/blimp/index. html

The Goodyear blimp is the Granddaddy of airships, if only because it’s been around the longest and has nearly universal consumer recognition. Here’s the skinny on flying the blimp, and an explanation of why your chances of getting to ride in it are about the same as winning the Super Lotto.

www. ohio. com/kr/blimp/blimp. htm

Here’s where the blimp yields its mystery. Find out what’s inside that big bag of gas that bobs over the ball game every weekend.

Flight Safety

airdisaster. com/

There’s no better aviation safety site on the Internet than this one. More readable than the National Transportation Safety Board’s site, and more richly layered. As with any site whose focus is airplane wrecks, it can be unnerving at times.

www. ntsb. gov/aviation/aviation. htm

This site provides a fountain of flight safety information and statistics that the American aviation industry relies on. Dense but rewarding.

General Aviation, Gliding, and Helicopters

www. avweb. com/

AVweb is rapidly becoming the Web’s best source of flying news and information. Sign up for the weekly e-mail newsletter. www. aopa. oig/intlcx. shtml

The AOPA is one of the stalwarts of aviation. The organization tirelessly advocates for general aviation pilots, and they serve as one of the best conduits for information and education.

www. ssa. org/

The Soaring Society of America takes an active role in promoting the sport, including sponsoring clubs and hosting competitions. The result is a highly loyal membership. If soaring appeals to you, this site will give you all the information you need to get started, including a roster of training sites and plenty of information about soaring and gliding.

www. groenbros. com/

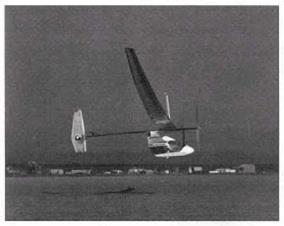

Groen Brothers company is working hard to develop a high-technology gyroplane, and it seems to be succeeding. Gyroplanes are regarded by some as a curiosity, but they have a lot of advantages over both airplanes and helicopters. Groen Brothers is adding a liberal helping of innovation to create what promises to be a remarkable family of aircraft.

Future of Aviation

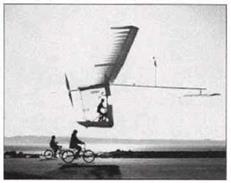

www. aerovironment. com/

This company is onto something big, if you ask me. Nothing rings cash registers nowadays like a technology that is highly advanced while remaining earth-friendly. Combine all that with the fact that these aircraft are being used as airborne telecommunications platforms, and you have some serious potential.

www. geocities. com/C apeC anaveral/9334/

This page, called “Blackbird—Past, Present & Future,” is enough to make some lovers of the “big iron” stand up and salute. The SR-71 is the biggest and baddest of a very tough breed. This site is the most complete and authoritative on the subject of the “Ablative Native” you’re going to find.

www. moller. com/skycar/index. html

Moeller Skycars are one of the dandiest vehicles to come down the pike in a long time. I can see the Moeller Skycars becoming the playthings of the very rich, but I have my doubts if they’ll be in most people’s price range for a while. According to the manufacturer, this little beauty cruises above the madding crowd at a cool 350 m. p.h. at a gas-sipping 15 miles per gallon. Can anybody lend me a million clams?

spaceflight. nasa. gov/index-m. html

When it comes to a manned space station, the future is today. Though it’s in its nascent stages in 2000, the International Space Station is growing one module at a time. For a tour of this “ultimate flying machine,” check out this excellent site.

www. scaled. com/

Burt Rutan’s company, Scaled Composites, is defining the leading edge of aerospace design. If you want to glimpse the airplane technology of tomorrow, snoop around this site.

www. solotrek. com/

I’d fly a SoloTrek in a New York minute, but something tells me this is going to be on the same list of dangerous luxuries as the Moeller Skycar. Still, we can dream, can’t we?

Golf (Gahlf)

Golf (Gahlf)