Proof Positive

The Wrights were prepared to prove their claim to be the first people to fly. They set up a camera and asked one of the members of the local rescue squad, or “Life Saving men,” as Orville called them, to snap the shutter once the Flyer flew off the ground. The man who snapped the picture was J. D. Daniel, and here’s what Orville wrote about that moment: “One of the Life Saving men snapped the camera for us, taking a picture just as the machine had reached the end of the track and had risen to a height of about two feet. The slow forward speed of the machine over the ground is clearly shown in the picture by Wilbur’s attitude. He stayed along beside the machine without any effort.”

|

Daniels had still more excitement ahead of him that day. Around noon, after the brothers had already made three more flights, the longest covering 850 feet in 59 seconds, a gust of wind began to overturn the Flyer while it was resting on the ground. Orville and Daniels raced to one rising wing and tried to hold it down. Orville lost his grip, but Daniels held on as the Flyer turned over and tumbled across the ground several times. Daniels was all right, but the Flyer was banged up so badly the brothers didn’t make any more flights that year.

Who Was Really First?

Almost from the time they first flew, it has been fashionable for iconoclasts to poohpooh the Wright brothers’ achievement in designing, testing, and flying the first airplane. Conspiracists, mostly in the camp of a German-born flying enthusiast named Gustave Whitehead, rail and protest against the bicycle makers, insisting that any

number of other people deserve the title of “first aviator.” Undoubtedly, a lot of the spite directed against the Wrights stemmed from the brothers’ 1906 patent of the Flyer, a move that many of their competitors saw as disrespectful of other pioneers whose research contributed to the Wrights’ success.

The most credible and dogged effort to dislodge the Wrights comes from Connecticut and the descendents of Gustave Whitehead. But why don’t you be the judge? Gustave Whitehead

Could a flyer have beaten the Wrights into the air by as much as four years? Hard to believe, but that was the claim of a German sailor turned concrete salesman named Gustave Whitehead. After shipwrecking in the Gulf of Mexico as a young man, Whitehead made two key decisions: to give up his job at sea and to settle in America. After wandering through Pennsylvania and the Northeast, Whitehead landed in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he worked as a mechanic and tinkered with flying machines. Whitehead had a talent for building engines, including the 10- horsepower acetylene motor that helped him make history’s first flight—if his story is to be believed.

|

Plane Talk Gustave Whitehead was so crazy about flying and parachuting even at a boy that he early on earned the nickname "The Flyer." The nickname it ironic, considering that the airplane that he thought helped the Wright brothers steal his place in history was also named the Flyer. |

In 1901, Whitehead claimed, he flew for the second time (that’s right, second time), a half-mile jaunt that came off uneventfully, or so The New York Herald reported shortly after the August 14 flight. On the same day. The Boston Transcript reported the very same flight, citing details that were nearly identical to those reported in The Herald. News reports published five days after the Bridgeport flight summed up the event: “Last week Whitehead flew in his machine half a mile.” According to the newspaper, the flight was flawless.

|

|

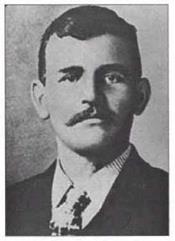

German-born Connecticut mechanic Gustave

Whitehead claimed to have beaten the Wright

brothers into the air by several years, and

he still has plenty of believers.

|

|