Ralph Johnstone

Ralph Johnstone, the performer who engaged in mock air battles with Arch Hoxsey, was a veteran performer, having toured America and Europe as a trick cyclist on the Vaudeville circuit. Although he was a far more cautious pilot than the brash Hoxsey, Johnstone also knew how to thrill audiences with his flying skill. Johnstone met a grislier end than most of his comrades who died while performing aviation stunts.

During a 1910 show in Denver, Johnstone was flying about 800 feet above the ground when his airplane broke up. As he struggled to gain control of the plane, he was tossed from his seat, which, like all airplane seats at the time, wasn’t equipped with a seat belt.

Johnstone’s luck held, however, at least for the moment. As he was falling overboard he stopped his fall when he reached out and grasped a strut. He hung on desperately as the plane sped toward the ground and crashed. The spectators were horror-struck, but recovered their senses in time to rifle the bloody body for souvenirs of gloves and pieces of clothing.

|

The Vin Fiz Falls Flat

By the Book Barnstormer was the name given to the swaggering and sometimes unsavory pilots who swooped down past barnyards and farmhouses to signal to everyone for miles around that airplane rides were being sold. |

With their breakneck antics, the early barnstormers managed to plant seeds in our collective psyche that made flying appear to be a life-and-death struggle with the elements. Though that may have been an accurate description in the early years of aviation, flying today is far from the dangerous pastime that it once was, and modern pilots are a bit less swashbuckling.

There may never have been a pilot more dashing than Cal Rodgers, but as most of those who shared the skies with him, he died young and he died in an airplane. Still, it was Rodgers who first proved to a skeptical American public that flying could progress beyond a death sport to become a viable way of getting from one side of the continent to the other.

Spurred by a $50,000 prize offered by publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst to the first flyer who could complete a coast-to-coast flight, Rodgers and a handful of other pilots signed up in 1911 to hopscotch across a country where airplanes were almost as unfamiliar as flying saucers and where airfields were all but nonexistent. The Hearst prize imposed a 30-day time limit, a daunting challenge in 1911.

Part of Rodgers’ appeal during his grueling cross-country race was the name of his Wright EX (for “Experimental’) biplane: the Vin Fiz. In exchange for emergency money—and he’d need all of that—Rodgers agreed to advertise Armour’s new grape soda on his plane by painting Vin Fiz across the bottom of his wings. As it turned out, the Vin Fiz people might have got a better value for their marketing dollars if Rodgers had emblazoned the slogan on the sides of his plane; he spent far more time grounded than he did aloft.

All told, in his trip across the country, Rodgers survived 14 minor crashes, five total crackups, uncounted engine failures in flight, an in-flight scalding when an engine hose sprayed loose, and a head-on collision with a chicken coop. Finally, with the Pacific Ocean finish line in sight after 49 days of misery and near-fatal accidents, he crashed again on the final leg from Pasadena to the beach. This time he crushed the bones in his ankle; the injury required a month to heal.

At last, 84 days—nearly three months—after leaving New York, Rodgers rolled the wheels of the Vin Fiz into the surf of the Pacific Ocean, carrying only a rudder and an oil pan from the original plane. Everything else had been destroyed and replaced en route.

|

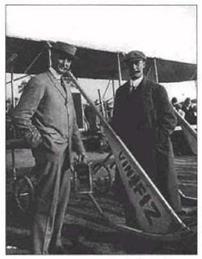

Cal Rodgers (right) completed a grueling cross country flight in 1911 in hopes of winning $50,000 He didn’t even come close to completing the flight in the allotted time, but he was the only flyer to actually finish the flight. He died in a plane accident shortly afterward. |

Because he badly overshot Hearst’s 30-day deadline, Rodgers was left empty-handed in Los Angeles. But he had movie-star looks and enough personality to charm a curious nation. Even if technically Rodgers’s flight was a failure, it was successful in that it—and Rodgers—turned America’s eyes toward the possibility of commercial aviation.

Four months after finishing the Vin Fiz tour, and almost on the very spot where he made his final landing at the end of that adventure, Rodgers flew his Wright EX into a flock of gulls—apparently in a deliberate show of bravado. One of the gulls jammed his rudder and caused the plane to fall out of control. Rodgers died of a broken back and a broken neck.

His tombstone reads, with characteristic flair:“I endure—I conquer.”