Ready for Takeoff

By the end of 1903, after years of testing wings and models in wind tunnels and ofjumping off sand dunes strapped to their gliders, the brothers were ready to try to fly. They had combined an airframe, an engine, and two propellers that they hoped would do what they wanted: maintain level flight in a machine they could steer and control. Even if they had no idea how to land the thing, the Wrights would at least start learning to control it in the air.

|

Plane Talk Three seb of control surfaces combine to allow pilots to smoothly maneuver in the air. Ailerons, the hinged vanes near the bp of both wings, move in opposite erections from each other and are responsible for turning the airplane left or right The elevators, the hinged vanes on the rear edge of the horizontal stabilizer, allow the pilot to move the nose up or down. The rudder, which is attached to the vertical stabilizer, helps pilots control the direction the nose points in and, in coordinab’on with the ailerons, has a subtle role in turning the plane. We’ll learn all about these different control surfaces in Chapter 7, "How Airplanes Fly, Part I: The Parts of a Plane." |

The first attempt to get the Flyer off the ground came in mid – December 1903, and ended in a crack – up. Wilbur won a coin-toss for the chance to make the first flight in the Flyer which the brothers had equipped with a 12-horsepower motor that turned two handmade propellers. Wilbur climbed in and layed flat on the bottom of the plane’s two wings, and Orville pushed the plane along the monorail track built on the sand. The plane lifted off the ground, but it stayed in the air for just a couple of seconds before it crashed into the sand. Wilbur wasn’t injured too badly, but the airplane needed two days’ worth of repairs. When it was finally put back together, it was Orville’s turn at the controls.

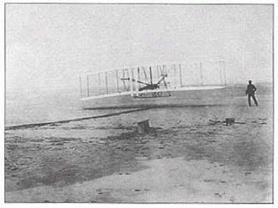

On the next flight attempt, Orville pushed the Wrights’ home-built engine to full throttle, and with Wilbur at the wingtip to steady the plane, rolled off down the monorail track. Almost exactly where the brothers calculated it would, the 700-pound Flyer lifted off the rail and flew unsteadily into a 20 m. p.h. wind. Orville controlled the plane’s bank by warping the wingtips using cables connected to a sort of steering wheel. And he kept it straight and level using a combination of rudder and elevator.

|

|

Twelve seconds later and 120 feet down the beach, Orville let the Flyer settle back to the sand, bringing an end to the first controlled, heavier-than-air flight and sparking a technological revolution that would change the world.

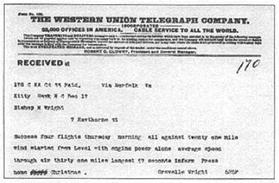

The Wrights sent their family in Dayton a telegram announcing their success. It was sent without punctuation and with some eccentric capitalization: “Success

|

With local resident J. D. Daniels manning the camera, Orville Wright

becomes the first human to make a sustained, controlled flight,

while his brother Wilbur helps steady the wings.

|

|

The Wrights were no fools. They established concrete proof of their history-making

flight by dashing off a telegram, which set them firmly in the history books,

but didn’t exactly impress everyone back home in Dayton, Ohio.