Circulation

An interesting way of thinking about the airflow over wings and wing-tip vortices is the theory of circulation. The fact that the air is speeded up over the upper surface, and slowed down on the under surface of a wing, can be considered as a circulation round the wing superimposed upon the general speed of the airflow (this does not mean that particles of air actually travel round the wing). This circulation is, in effect, the cause of lift. If we now consider this circulation as slipping off each wing tip, and continuing downstream, we have the wing-tip vortices; and they rotate, as already established, downwards behind the wing and upwards outside the wing tips.

But this is not all. When the wing starts to move, or when the lift is increased, the wing sheds and leaves behind a vortex rotating in the opposite direction to the circulation round the wing – sometimes called the starting vortex – so there is a complete system of vortices, round the wing, then the wing-tip vortices, and finally the starting vortex. The wing-tip vortices and the starting vortex are gradually damped out with time – owing to viscosity – but the exertion of engine power (which ultimately is what creates the vortices, and so the lift and induced drag) keeps renewing the circulation round the wing, and the wing-tip vortices which result from it.

This is not just a theory; the flow over the wing can be clearly seen in experiments, as can the wing-tip vortices, while the starting vortex is easily demonstrated by starting to move a model wing, or even one’s hand, through water. But perhaps the most extraordinary example of the reality of the effect of aspect ratio on circulation and wing-tip vortices is that by clever formation flying of say three or five aircraft, with the centre one leading, and the outer ones with their wing tips just behind the opposite wing tips of the

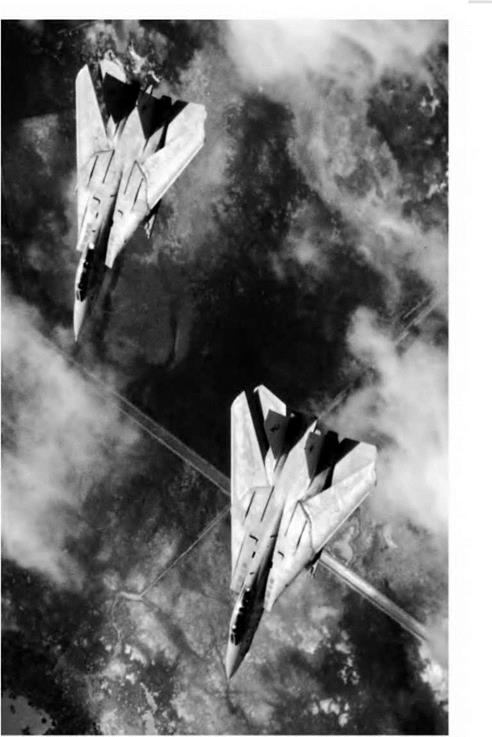

Fig3E Low aspect ratio (opposite)

(By courtesy of the Grumman Corporation, USA)

For high-speed flight, the wings of the FI4 are swung back producing an aspect ratio of less than 1. For low-speed flight they can be swung forward giving a higher aspect ratio.

|

|

leading aircraft, it is possible to achieve something of the same result (which is illustrated in flying for maximum range) as with an aircraft of three or five times the span! This is hardly a practical proposition for flying across the Atlantic, but it has been illustrated by careful experiment, and geese and other birds used the technique long before we discovered it!