Choice of powerplant

Although the jet engine has now been around for more than half a century, virtually all small private aircraft are still powered by reciprocating petrol (gasoline) engines driving propellers. Large commercial transport and military aircraft are predominantly propelled by turbo-jet or turbo-fan engines, while for the intermediate size of civil aircraft, ranging from small executive transports to short-haul feeder airliners, a gas-turbine driving a propeller is frequently chosen. The reason for these divisions will be seen from the descriptions that follow.

Reciprocating engines

Small reciprocating engines can produce a surprisingly large amount of power in relationship to their size. A large model aircraft engine can produce about 373 W (0.5 bhp), which is rather more than the power that a good human athlete can sustain for periods exceeding one minute. A problem arises, however, when an engine is required for a very large or fast aircraft, where a considerable amount of power is required.

If we simply tried to scale up a typical light aircraft engine, the stresses due to the inertia of the reciprocating parts would also increase with scale, and we would very soon find that there was no material capable of withstanding such stresses. This is because the volume, and hence, the mass and inertia of the rotating parts, increases as the cube of the size, whereas, the cross-sectional area only increases as the square.

The way to overcome this problem is to keep the cylinder size small, but to increase the number of cylinders. Thus, whereas a light aircraft will normally have four or six cylinders, the larger piston-engined airliners of the 1940s and 1950s frequently used four engines with as many as 28 cylinders each. The complexity of such arrangements leads to high costs, both in initial outlay, and in servicing. To get some idea, try working out how long it would take you to change the sparking plugs in an aircraft with four engines of 28 cylinders each, and two plugs per cylinder. Do not forget to allow some time for moving the ladders.

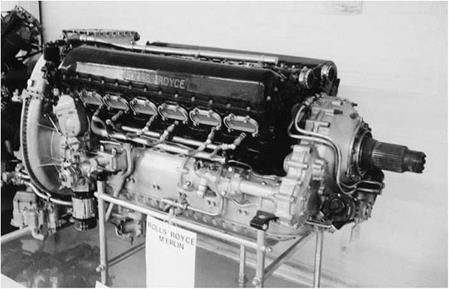

Many arrangements of cylinders were tried, in order to devise a convenient, compact and well balanced configuration. By the end of the era of the large piston engines, in the early 1950s, two types predominated; the air-cooled radial, and the in-line water-cooled V-12. The latter is typified by the Rolls – Royce Merlin (Fig. 6.15), which was used on many famous allied aircraft of the Second World War, including the Spitfire and Mustang. Water-cooling was used on the in-line V-12 engines, because of the difficulties of producing even cooling of all cylinders with air. Modern light aircraft engines are normally aircooled, with four or six cylinders arranged in a flat configuration.

|

Fig. 6.15 The classic liquid-cooled V-12 Rolls-Royce Merlin, which propelled many famous allied aircraft during the Second World War, including the Spitfire and Mustang. A large supercharger is fitted |