The aerofoil section

Although wings consisting of thin flat or curved plates can produce adequate lift, it is difficult to give them the necessary strength and stiffness to resist bending. Early aircraft that used plate-like wings with a thin cross-section, employed a complex arrangement of external wires and struts to support them, as seen in Figs 1.7(a) and 1.7(b). Later, to reduce the drag, the external wires were

|

|

|

|

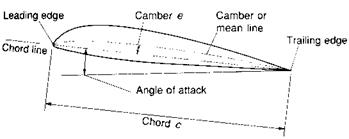

Fig. 1.8 Cambered aerofoil The degree of camber is usually expressed as a percentage of the chord. (e/c) x 100% |

removed, and the wings were supported by internal spars or box-like structures which required a much thicker wing section. By this time, it had in any case been found that thick ‘aerofoil section’ shapes, similar to that shown in Fig. 1.5(a), had a number of aerodynamic advantages, as will be described later.

The angle at which the wing is inclined relative to the air flow is known as the angle of attack. The term incidence is commonly used in Britain instead, but in American usage (and in earlier British texts), incidence means the angle at which the wing is set relative to the fuselage (the main body). We shall use the term angle of attack for the angle of inclination to the air flow, since it is unambiguous.

The camber line or mean line is an imaginary line drawn between the leading and trailing edges, being at all points mid-way between the upper and lower surfaces, as illustrated in Fig. 1.8. The maximum deviation of this line from a straight line joining the leading and trailing edges, called the chord line, gives a measure of the amount of camber. The camber is normally expressed as a percentage of the wing chord. Figure 1.5 shows examples of cambered sections. When the aerofoil is thick and only a modest amount of camber is used, both upper and lower surfaces may be convex, as in Fig. 1.8.

A typical thick cambered section may be seen on the propeller-driven transport aircraft of the early postwar period, in Fig. 1.9. Nowadays, various forms of wing section shape are used to suit particular purposes. Interestingly, interceptor aircraft use very thin plate-like wings, with sections that are considerably thinner than those of the early biplanes.

Before we can continue with a more detailed description of the principles of lifting surfaces, we need to outline briefly some important features of air and air flow.