The Future of Aviation

|

|

|

Of all the forms of transportation humans have devised, none have progressed as far and as fast as aviation. If we consider the Wright brothers’ flight in 1903 as the birth of modern aviation, it’s taken just under a century for airplanes to evolve from a curious spectacle to a force powerful enough to send craft into space.

Indeed, the space shuttle—in effect a highly specialized glider—is capable of space flight for days or weeks at a time. It acts as a sort of ultra-high-tech ferry, rocketing people and material up to an international space station—a space station that, within a few years, will feature living and working pods for seven researchers and scientists who will stay in space for up to six months at a time.

It’s nearly impossible to believe that the men and women who will soon spend parts of their lives skimming hundreds of miles above the earth can trace their legacy fewer than 10 decades back to the bishop’s boys, Wilbur and Orville, and their experiments on wind-blown Kill Devil Hill.

Human Wings

Flying has always been a very personal means of expression. Even the most mechanized and regimented of all aspects of aviation, military flying, allows its pilots to express themselves with a flourish of skill or a touch of grace.

For years, airplane designers have been working on human-powered craft to bring man closer to the ultimate dream of flying as naturally as the birds. Human- powered flight, which, as its name implies, uses no power source other than human muscle, appears to be a reversion rather than a step forward in the technology of flight. But when considered as the realization of the centuries-old dream of taking to the air as easily as birds, it represents possibly the most sublime evolution in aviation.

Because humans are poor sources of power, creating only about % horsepower at best, the goal of creating an airplane that can lift its own weight and that of its pilot was beyond most designers’ abilities—and then ultra-lightweight composite materials were created.

|

At Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, pilot Glenn Tremml flew the humanpowered airplane Daedalus 88. (NASA) |

Paul MacCready

One man, Paul MacCready, deserves credit for most of the advances in design and lightweight materials that have made human-powered flight possible. He also deserves credit for devising innovative ways to use old-fashioned material to bring out its hidden strength without adding weight.

|

Plane Talk As proof that a talented designer doesn’t have to shackle himself to any one pursuit, Paul MacCready’s portfolio includes the design of General Motors’ Impact automobile, which is solar powered. He also designed and flew the radio-controlled pterodactyl model that was featured in the IMAX film On the Wing. |

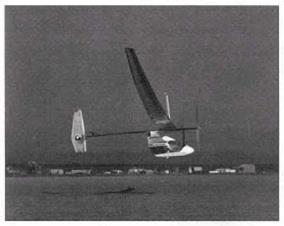

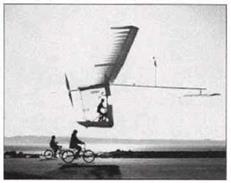

For example, MacCready’s first successful human-powered plane, the Gossamer Condor, used only cardboard and balsa wood as structural material, and weighed only 70 pounds empty, but it was able to carry a pilot that weighed more than the plane did. The Gossamer Condor, whose 96-foot wingspan was wider than a DC-9 jetliner’s wings, was the first plane to maneuver around a mile-long figure-eight course powered only by human muscle.

|

In a photograph reminiscent of the photo of the Wright brothers’ liftoff on December 17, 1903, Paul MacCready’s Gossamer Albatross lifts off for a flight in 1980. (NASA) |