Mass balance

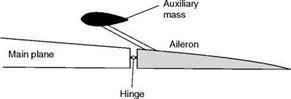

Control surfaces are often balanced in quite a different sense. A mass is fitted in front of the hinge. This is partly to provide a mechanical balancing of the mass of the control surface behind the hinge but may also be partly to help prevent an effect known as ‘flutter’ which is liable to occur at high speeds (Fig. 9.19). This flutter is a vibration which is caused by the combined effects of the changes in pressure distribution over the surface as the angle of attack is altered, and the elastic forces set up by the distortion of the structure itself. All structures are distorted when loads are applied. If the structure is elastic, as all good structures must be, it will tend to spring back as soon as the load is removed, or changes its point of application. In short, a distorted structure is like a spring that has been wound up and is ready to spring back. An aeroplane wing or fuselage can be distorted in two ways, by bending and by twisting, and each distortion can result in an independent vibration. Tike all vibrations, this flutter is liable to become dangerous if the two effects add up. The flutter may affect the control surfaces such as an aileron, or the main planes, or both. The whole problem is very complicated, but we do know of two features which help to prevent it – a stiff structure and mass balance of the control surfaces. When the old types of aerodynamic balance were used, e. g. the inset hinge or horn balance, the mass could be concealed inside the forward portion of the control surface and thus two birds were killed with one stone; but when the tap type of balance is used alone the mass must be placed on a special arm sticking out in front of the control surface. In general, however, the problems of flutter are best tackled by increasing the rigidity of the structure and control-system components.

Targe aircraft and military types now invariably have powered controls and these are much less sensitive to problems of flutter as the actuating system is very rigid.

Perhaps it should be emphasised that the mass is not simply a weight for the purpose of balancing the control surface statically, e. g. to keep the aileron floating when the control mechanism is not connected; it may have this effect, but it also serves to alter the moments of inertia of the surface, and thus alter the period of vibration and the liability to flutter. It may help to make this clear

|

|

|

|

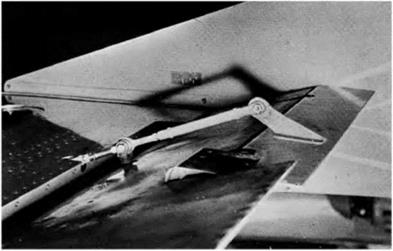

Fig 91 Tab control mechanism (By courtesy of Piaggio, Genoa, Italy)

if we realise that mass balance is just as effective on a rudder, where the weight is not involved, as on an elevator or aileron.

On old military biplane aircraft, the exact distribution of mass on the control surfaces was so important that strict orders had to be introduced concerning the application of paint and dope to these surfaces. It is for this reason that the red, white and blue stripes which used to be painted on the rudders of Royal Air Force machines were removed (they were later restored, but only on the fixed fin), and why the circles on the wings were not allowed to overlap the ailerons. Rumour has it that when this order was first promulgated, some units in their eagerness to comply with the order, but ignorant as to its purpose, painted over the circles and stripes with further coats of dope!