Theories and Conspiracies

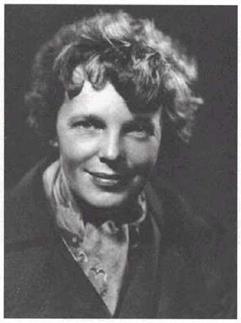

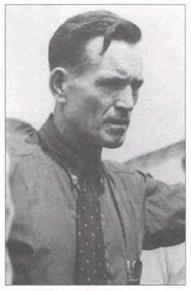

What happened on that final flight? Following are the theories—ranging from most probable to highly unlikely—behind the disappearance of Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan. Which one do you believe—or could there be still another explanation?

• Earhart and Noonan ran out of gas and ideas. After nearly 20 hours of flying, Earhart simply couldn’t find Howland Island, which would have been a speck of land in a trackless ocean. She was forced to ditch the plane into the sea, and was killed or drowned in the crash or managed to scramble into a life raft before dying of exposure.

• Earhart and Noonan were in no condition to continue flying. There’s no doubt that Earhart was exhausted after she and Noonan had flown 22,000 miles around the globe to reach Lae. At every stop they had been hounded by reporters, fascinated gawkers, and clumsy customs procedures. On top of all

that, Earhart might have been pregnant at the time; another theory goes that she may have been suffering from premature menopause. On top of those mutually exclusive possibilities is that Noonan may have been drinking again, and may have been in no condition to navigate a plane to a pinpoint target in a vast ocean.

|

On Course Hollywood has also been caught up in the crusading life and mysterious disappearance of Amelia Earhart. Two television films about Earhart have been made, one released in 1976 starring Susan Clark called Amelia Earhart and another in 1994, starring Diane Keaton, called Amelia Earhart: The Final Flight. Both give excellent insights into Earhart’s life and mysterious death. |

• Earhart was on a spy mission. President Franklin D. Roosevelt badly wanted to know what the Japanese were up to in the South Pacific as the Land of the Rising Sun became increasingly hostile to American ally China. The theory goes that he recruited Earhart to photograph Japanese ship movements, perhaps causing her to stray off course and get lost. Conspiracists say the unbelievably long “search mission” provided cover for more military spying.

• Earhart became a propaganda tool. Captured by the Japanese during a surveillance mission, Earhart was brought to the Japanese mainland and forced to broadcast to American forces during World War II under the name “Tokyo Rose.”

• Earhart died of disease. Forced down on the island of Saipan, then controlled by the Japanese, Earhart died of dysentery and Noonan was beheaded. A different slant on that theory goes that Earhart survived the crash and the Japanese authorities, married a native, and lived happily in anonymity.

• Earhart’s navigator missed Howland Island and drifted to Nikumaroro Island, 425 miles southeast. There, after ditching on a reef, the ill-fated pair succumbed to thirst and tropical heat.

• The Roosevelt administration hid Earhart and Noonan on Britain’s Hull Island. A lost-at-sea story was concocted to cover a spy mission. Both aviators died in hiding.

• She lived out her life in Saipan. One disappearance theory holds that Earhart and Noonan purposely flew into Japanese-controlled territory around the islands of Micronesia in an attempt to spy on Japanese activity around Truk Island. The Japanese captured them and held them captive on Saipan, where both later died.

• She lived out her life in New Jersey. This theory is one of the most outlandish, as Earhart was a very well-known celebrity who would be recognized instantly wherever she went.

|

Theories continue to swirl around Amelia Earhart more than 60 years after her disappearance. What, or who, was really to blame? |