The Crossover Model and Pilot-Induced Oscillations

The crossover model has proved to be of great value in understanding pilot-induced oscillations. The way has been opened for validating empirical corrections for the phenomenon, such as described by Phillips, and for the development of new concepts in the area and superior flying qualities designs.

Duane McRuer provides a comprehensive survey of pilot-induced oscillations in a report for the Dryden Flight Research Center (McRuer, 1994). Having been experienced by the Wright brothers, pilot-induced oscillations qualify as the senior flying qualities problem. Recent dramatic flight experiences, combined with the availability of advanced analysis methods, have given the subject fresh interest. Between the years 1947 and 1994, there were over 30 very severe reported cases, in airplanes ranging from a NASA paraglider to the space shuttle Orbiter. McRuer proposes three pilot-induced oscillation categories, as follows:

essentially linear;

quasi-linear, with surface rate or position limiting;

essentially nonlinear, including pilot or mode transitions.

|

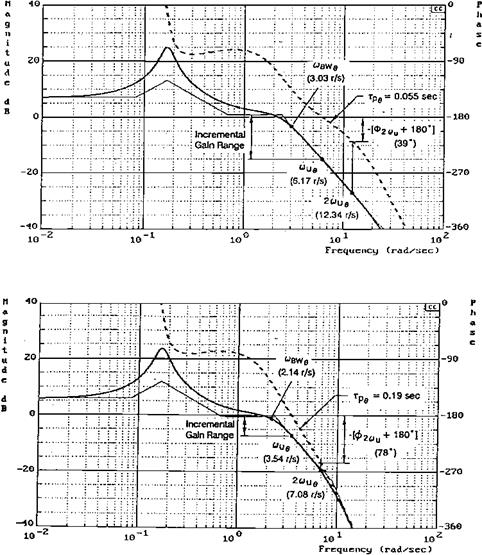

Figure 21.4 Pilot-airplane open-loop frequency responses for two configurations of the USAF/ Calspan variable-stability T-33. The upper case, with no pilot-induced oscillations, has the ideal integrator shape in the vicinity of crossover. The lower case, with severe pilot-induced oscillations, has a steeper slope and more phase lag at high frequencies. (From McRuer, STI Technical Rept. 2494-1, 1994) |

An important validation of the crossover model approach to the first category was furnished by analysis of fully developed pilot-induced oscillations on the USAF/Calspan variable-stability NT-33 (Bjorkman, 1986). In six severe cases there were large effective open-loop system delays, departing from the ideal integrator-type airframe transfer function in the region of crossover (Figure 21.4). The required pilot dynamics for compensatory operation thus required

a great deal of pilot lead as well as exquisitely precise adjustment of pilot equalization and gain to approximate the crossover law and to close the loop in a stable manner.

Linear pilot-induced oscillations include complex interactions with airplane flexible modes. Mode-coupled oscillations have been experienced on the F-111, the YF-12, and the Rutan Voyager. Control surface rate-limiting pilot-induced oscillations were discussed previously.

Essentially nonlinear pilot-induced oscillations have arisen chiefly in connection with pilot and mode transitions. In one such case, weight-on-wheel and tail strike switches changed the stability augmentation control laws on the Vought/NASA fly-by-wire F-8, presenting the pilot with a rapid succession of different dynamics (McRuer, 1994). The pilot was unable to adapt in time. Mode transitions, either as a function of pilot input amplitude or automatic mode changes, are a particular source of pilot-induced oscillations in modern fly-by-wire flight control systems. The importance of avoiding pilot-induced oscillations on fly-by-wire transport airplanes led to the study discussed in Sec. 11.