Moving Through a Constant-Density Fluid Without Circulation

This section reviews some interesting results of incompressible flow theory which highlight the similarities between the dynamics of a rigid body and constant-density flow. They are particularly useful when calculating the resultant forces and moments exerted by the fluid on one or more bodies moving through it. Consider a particular solid body S of the type discussed above. Let there be a set of portable axes attached to the body with origin at O’; г is the position vector measured instantaneously from O’. Let u(<) and w(t) denote the instantaneous absolute linear and angular velocity vectors of the solid relative to the fluid at rest at infinity. See Fig. 2-2. If n is the outward normal to the surface of S, the boundary condition on the velocity potential is given in terms of the motion by

ЗФ

T – = [u + w X r] • n = u • n —(— и ■ (г X n) on S = 0. (2-33)

In the second line here the order of multiplication of the triple product has been interchanged in standard fashion.

Now let Ф be written as

Ф = u – ф + ы-Х. (2-34)

Ф = u – ф + ы-Х. (2-34)

Assuming the components of the vectors ф and X to be solutions of Laplace’s equation dying out at infinity, the flow problem will be solved if these coefficients of the linear and angular velocity vectors are made to satisfy the following boundary conditions on S:

P – = г X n. (2-36) dn

Evidently ф and X are dependent on the shape and orientation of S, but not on the instantaneous magnitudes of the linear and angular velocities themselves. Thus we see that the total potential will be linearly dependent on the components of u and w. Adopting an obvious notation for the various vector components, we write

Turning to (2-11), we determine that the fluid kinetic energy can be expressed as

T = ~ f + г)] dS

s s

= + Bv2 + Cw2 + 2 A’vw + 2B’wu + 2C’uv

+ Pp2 + Qq2 + Rr2 + 2 P’qr + 2Q’rp + 2 R’pq + 2 p[Fu + Gv + Hw) + 2q[F’u + G’v + H’w]

+ 2r[F"u + G"v + H"w]}. (2-38)

Careful study of (2-37) and the boundary conditions reveals that A, B, C, . . . are 21 inertia coefficients directly proportional to density p and dependent on the body shape. They are, however, unaffected by the instantaneous motion. Therefore T is a homogeneous, quadratic function of u, v, w, p, q, and r.

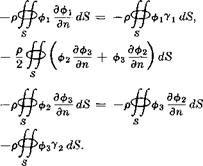

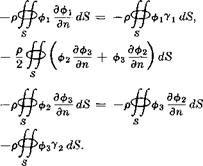

By using (2-35) and (2-36) and the reciprocal theorem (2-12), the following examples can be worked out without difficulty:

(2-39)

(2-39)

(2-40)

Here 71 and 72 are the direction cosines of the unit normal with respect to the x – and у-axes, respectively.

Some general remarks are in order about the kinetic energy. First, we observe that the introduction of more advanced notation permits a systematization of (2-38). Thus, in terms of matrices,

The first and last factors here are row and column matrices, respectively, while the central one is a 6 X 6 symmetrical square matrix of inertia coefficients, whose construction is evident from (2-38). In the dyadic or tensor formalism, we can express T

Ї1 — • M • u “T u • S • ш – j – 2^ • I * w. (2—42)

Here M and I are symmetric tensors of “inertias ” and “moments of inertia, ” while S is a nonsymmetrical tensor made up of the inertia coefficients which couple the linear and angular velocity components. For instance, the first of these reads

M = Aii + 5jj + Ckk + A'[ jk + kj] + B'[lsi + ik] + C'[ij + ji],

(2-43)

(Of course, the tensor summation notation might be used in place of dyadics, but the differences are trivial when we are working in Cartesian frames of reference.)

It is suggestive to compare (2-38) with the corresponding formula for the kinetic energy of a rigid body,

Ti = mu2 + v2 + w2] + %[p2Ixx + q2Ivy + r2Izz]

— [Iyzqr – F Izxrp + IxyPq]

+ m{x(vr — ivq) + 1j(wp — ur) + z(uq — vp)}. (2-44)

Here standard symbols are used for the total mass, moments of inertia, and products of inertia, whereas x, y, and z are the coordinates of the center of gravity relative to the portable axes with origin at O’. For many purposes, it is convenient to follow Kirchhoff’s scheme of analyzing the motion of a combined system consisting of the fluid plus the solid body. It turns out to be possible to derive Lagrangian equations of motion for this combined system, which are little more complex than those for the solid alone.

Another important point concerns the existence of principal axes. It is well known that the number of inertia coefficients for the rigid body can be reduced from ten to four by working with principal axes having their origin at the center of gravity. By analogy with this result, or by reference to the tensor character of the arrays of inertia coefficients, one can show that an appropriate rotation of axes causes the off-diagonal terms of M to vanish, while a translation of the origin O’ relative to S converts I to a diagonal, thus reducing the 21 to 15 inertia coefficients. Sections 124 to 126 of Lamb (1945) furnish the details.

For present purposes, we focus on how the foregoing results can be used to determine the forces and moments exerted by the fluid on the solid.

It is a well-known theorem of dynamics, for a system without potential energy, that the instantaneous external force F and couple M are related to the instantaneous linear momentum £ and angular momentum Л by

Furthermore, these momenta are derivable from the kinetic energy by equations which may be abbreviated

dTi

dTi

дш

The notation for the derivatives is meaningful if the kinetic energy is written in tensor form, (2-42). To assist in understanding, we write out the component forms of (2-47),

|

£1 = dTi/du, £2 = dTi/dv, £3 = dTi/dw. (2-49a, b,c)

|

Lagrange’s equations of motion in vector notation are combining (2-45) through (2-48), as follows:

|

derived by

|

|

^5

II

|

(2-50)

|

|

— !(£)•

|

(2-51)

|

|

The time derivatives here are taken with respect to a nonrotating, nontranslating system of inertial coordinates. Some authors prefer these results in terms of a time rate of change of the momenta as seen by an observer rotating with a system of portable axes. If this is done, and if we recognize that there can be a rate of change of angular momentum due to a translation of the linear momentum vector parallel to itself, we can replace (2-45) and (2-46) with

|

|

(2-52)

|

|

(2-53)

|

|

The subscript p here refers to the aforementioned differentiation in portable axes. Corresponding corrections to the Lagrange equations are evident.

Since the foregoing constitute a result of rigid-body mechanics, we attempt to see how these ideas can be extended to the surface S moving through an infinite mass of constant-density fluid. For this purpose, we associate with £ and X the impulsive force and impulsive torque which would have to be exerted over the surface of the solid to produce the motion instantaneously from rest. (Such a combination is referred to as a “wrench.”) In view of the relationship between impulsive pressure and velocity potential, the force and torque can be written

These so-called “Kelvin impulses” are no longer equal to the total fluid momenta; the latter are known to be indeterminate in view of the nonvanishing impulses applied across the outer boundary in the limit as it is taken to infinity. Nevertheless, we shall show that the instantaneous force and moment exerted by the body on the liquid in the actual situation are determined from the time rates of change of £ and X.

To derive the required relationship, we resort to a partially physical reasoning that follows Chapter 6 of Lamb (1945). Let us take the linear force and linear impulse for illustration purposes and afterwards deduce the result for the angular quantities by analogy.

Consider any flow with an inner boundary S and an outer boundary 2, which will later be carried to infinity, and let the velocity potential be Ф. Looking at a short interval between a time t0 and a time t, let us imagine that just prior to t0 the flow was brought up from rest by a system of impulsive forces (—рф0) and that, just after t1: it was stopped by —(—рФі). The total time integral of the pressure at any point can be broken up into two impulsive pieces plus a continuous integral over the time interval.

The first integral on the right here vanishes because the fluid is at rest prior to the starting impulse and after the final one. Also these impulses make no appreciable contribution to the integral of Q2/2.

Suppose now that we integrate these last two equations over the inner and outer boundaries of the flow field, simultaneously applying the unit normal vector n so as to get the following impulses of resultant force at these boundaries:

We assert that each of these impulses must separately be equal to zero if the outer boundary 2 is permitted to pass to infinity. This fact is obvious if we do the integration on the last member of (2-57),

The integral of the term containing the constant in (2-57) vanishes since a uniform pressure over a closed surface exerts no resultant force. Furthermore, the integral of Q2/2 vanishes in the limit because Q can readily be shown to drop off at least as rapidly as the inverse square of the distance from the origin. The overall process starts from a condition of rest and ends with a condition of rest, so that the resultant impulsive force exerted over the inner boundary and the outer boundary must be zero. Equation (2-58) shows that this impulsive force vanishes separately at the outer boundary, so we are led to the result

f[nf‘1+ pdtdS = 0. (2-59)

a

In view of (2-59), the right-hand member of (2-56) can then be integrated over S and equated to zero, leading to

Jjnj*1 pdtdS = f^^dt = jj[—рФі — (—рФ0)]пй5 = ki ~ 5o-

s ° ° s (2-60)

Finally, we hold t0 constant and differentiate the second and fourth members of (2-60) with respect to fi. Replacing <i with t, since it may be regarded as representing any given instant, we obtain

F = f – (2-61)

This is the desired result. It is a simple matter to include moment arms in the foregoing development, thus working with angular rather than

linear momentum, and derive

where Л is the quantity defined by (2-55). The instantaneous force and instantaneous moment about an axis through the origin O’ exerted by the body on the fluid are, respectively, F and M.

If we combine with the foregoing the considerations which led to (2-52) and (2-53), we can reexpress these last relationships in terms of rates of change of the Kelvin linear and angular impulses seen by an observer moving with the portable axes,

(2-63)

(2-64)

As might be expected by comparison with rigid body mechanics, fj and can be obtained from the fluid kinetic energy T. The rather artificial and tedious development in Lamb (1945) can be bypassed by carefully examining (2-38). The integrals there representing the various inertia coefficients are taken over the inner bounding surface only, and it should be quite apparent, for example, that the quantity obtained by partial differentiation with respect to и is precisely the ж-component of the linear impulse defined by (2-54); thus one finds

The dyadic contraction of these last six relations is, of course, similar to (2-47) and (2-48).

Suitable combinations between (2-65)-(2-66) and (2-61)-(2-64) can be regarded as Lagrange equations of motion for the infinite fluid medium bounded by the moving solid. For instance, adopting the rates of change as seen by the moving observer, we obtain

In the above equations, Fbody and Mbody are the force and moment exerted by the fluid on the solid, which are usually the quantities of interest in a practical investigation.

2-5 Some Deductions from Lagrange’s Equations of Motion in Particular Cases

In special cases we can deduce a number of interesting results by examining (2-67)-(2-68) together with the general form of the kinetic energy, (2-38).

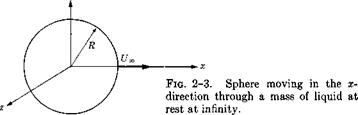

1. Uniform Rectilinear Motion. Suppose a body moves at constant velocity u and without rotation, so that и = 0. The time derivative terms in (2-67) and (2-68) vanish, and they may be reduced to

If body = 0, (2-69)

Mbody = – u X ~ ■ (2-70)

The fact that there is no force, either drag or lift, on an arbitrary body moving steadily without circulation is known as d’Alembert’s paradox. A pure couple is found to be experienced when the linear Kelvin impulse vector and the velocity are not parallel. These quantities are obviously parallel in many cases of symmetry, and it can also be proved that there are in general three orthogonal directions of motion for which they are parallel, in which cases the entire force-couple system vanishes. Similar results can be deduced for a pure rotation with u = 0.

2. Rectilinear Acceleration. Suppose that the velocity is changing so that u = u(t), but still w = 0. Then a glance at the general formula for kinetic energy shows that

дТ^.дТ. ЗГ ЭГ

5u 1 du ^ dv dw

= і [Am + C’v + B’w] + }[Bv – f A’w + C’u]

+ к[Cw + A’v + B’u] = M u. (2-71)

This derivative is a linear function of the velocity components. Therefore,

Fbody = – M ~ ■ (2-72)

For instance, if the acceleration occurs entirely parallel to the ж-axis, the force is still found to have components in all three coordinate directions:

рьjC’g-M’g. (2-73)

It is clear from these results why the quantities A, B, . . . , are referred to as virtual masses or apparent masses. In view of the facts that the

virtual masses for translation in different directions are not equal, and that there are also crossed-virtual masses relating velocity components in different directions, the similarity with linear acceleration of a rigid body is only qualitative.

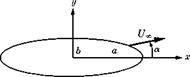

3. Hydrokinetic Symmetries. Many examples of reduction of the system of inertia coefficients for a body moving through a constant-density fluid will be found in Chapter 6 of Lamb (1945). One interesting specialization is that of a solid with three mutually perpendicular axes of symmetry, such as a general ellipsoid. If the coordinate directions are aligned with these axes and the origin is taken at the center of symmetry, we are led to

T = ЦАи2 + Bv2 + Cw2 + Pp2 + Qq2 + Rr2]. (2-74)

The correctness of (2-74) can be reasoned physically because the kinetic energy must be independent of a reversal in the direction of any linear or angular velocity component, provided that its magnitude remains the same. It follows that cross-product terms between any of these components are disallowed. Here we can see that a linear or angular acceleration along any one of the axes will be resisted by an inertia force or couple only in a sense opposite to the acceleration itself. This is a result which also can be obtained by examination of the physical system itself.

![]() 1

1![]()

![]()

![]() vV = v2

vV = v2 Fig. 2-і. Arbitrary point P in liquid flow produced by general motion of an inner boundary S.

Fig. 2-і. Arbitrary point P in liquid flow produced by general motion of an inner boundary S.![]() (2-24)

(2-24)![]()

![]() (2-31)

(2-31)![]() (2-32)

(2-32)

This stretching enables us to study the flow in the immediate neighborhood of the airfoil in the limit of e —> 0 since the airflow shape then remains independent of € (see Fig. 5-2) and the width of the inner region becomes of order unity. The zeroth-order inner term is that of a parallel flow, that is, Фо = x, because the inner flow as well as the outer flow must be parallel in the limit t —> 0.

This stretching enables us to study the flow in the immediate neighborhood of the airfoil in the limit of e —> 0 since the airflow shape then remains independent of € (see Fig. 5-2) and the width of the inner region becomes of order unity. The zeroth-order inner term is that of a parallel flow, that is, Фо = x, because the inner flow as well as the outer flow must be parallel in the limit t —> 0. where

where along the positive ж-axis and joined together by an infinitesimal piece along the y-axis, also of unit strength (see Fig. 5-4).

along the positive ж-axis and joined together by an infinitesimal piece along the y-axis, also of unit strength (see Fig. 5-4).

Ф = u – ф + ы-Х. (2-34)

Ф = u – ф + ы-Х. (2-34) (2-39)

(2-39)

![Thin Airfoils in Incompressible Flow Подпись: X2] FIG. 5-6. Integration path in the complex plane.](/img/3128/image248_0.gif)

For blunt shapes like the sphere, the results of potential theory do not agree well with what is measured because of the presence of a large separated wake to the rear, a problem which we discuss further in Chapter 3. It was this sort of discrepancy that dropped theoretical aerodynamics into considerable disrepute during the nineteenth century. The blunt-body flows are described here principally because they provide simple illustrations. When it comes to elongated streamlined shapes, a great deal of useful and accurate information can be found without resort to the nonlinear theory of viscous flow, however, and such applications constitute the ultimate objective of this book.

For blunt shapes like the sphere, the results of potential theory do not agree well with what is measured because of the presence of a large separated wake to the rear, a problem which we discuss further in Chapter 3. It was this sort of discrepancy that dropped theoretical aerodynamics into considerable disrepute during the nineteenth century. The blunt-body flows are described here principally because they provide simple illustrations. When it comes to elongated streamlined shapes, a great deal of useful and accurate information can be found without resort to the nonlinear theory of viscous flow, however, and such applications constitute the ultimate objective of this book.![Examples of Two - and Three-Dimensional Flows Without Circulation Подпись: — Theoretical (2-90) о Determined by integration FIG. 2-5. Comparison between predicted and measured moments about a cen- troidal axis on a prolate spheroid of fineness ratio 4:1. [Adapted from data reported by R. Jones (1925) for a Reynolds number of about 500,000 based on body length.]](/img/3128/image151_0.gif)